Technology has come a long way in the last few years: virtual reality; cloud computing; accessible 3D printing; 360-degree film; tablets; smart watches.

Ten years ago, the idea of augmented reality and smart gadgets was still firmly entrenched in the realm of science fiction – the gesture-controlled crime scene investigation of Minority Report and the engineering interface idealised in Iron Man were still seen as something a long way out of our current technological grasp.

We were wrong – or at least I was.

It’s the start of 2016 and Google Glass has been and gone, virtual reality headsets are set to enter the home, YouTube supports 360-video, and yesterday I saw a promotion of a wearable gesture-tracking controller that lets you “use the force” to control a Star Wars BB-8 toy droid. In Melbourne, entertainment company Zero Latency has opened a free-roam virtual reality entertainment centre and self-driving cars are being road tested in Adelaide.

It’s a glorious collision of the real and digital worlds, where digital technologies are breaking down barriers and changing how we communicate and process information. But, while a lot of hype for digital technology stems from the art and entertainment sector, it has potential in other fields too: healthcare, architecture, construction, science, archaeology, financial industries, education and business are all incorporating these new technologies to help workers visualise (or simulate) anything from market trends to a virtual rendering of a new apartment block.

In a small office in the upper echelons of building 208 that houses Curtin’s School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts, Associate Professor Artur Lugmayr is giving students a toolkit for this brave new world. As coordinator of Curtin’s visualisation and interactive media major – known as VisMedia – Lugmayr believes it is critical that the workforce has people who are skilled in developing, operating and communicating in interactive environments.

“Today pretty much everything is interactive,” he says. “When we look at web pages, everything is cooperative and social, with social media, crowd funding and all these notions.”

It extends beyond social media and entertainment, Lugmayr explains. Everything, from professional business to education to information management and IT systems, are, can or soon will be interactive. There’s the trend for smart environments to consider too, with smart fridges, cars and homes to become even more common in the next five to ten years.

“It’s an intelligent-medium environment and it’s important that students learn how to cope with these newly emerging technologies and how to make use of these technologies in a practical way. We teach them how to innovate, how to create new services and apply these across industries such as entertainment, health, business, and science.”

The major’s second component is visualisation. Visualisation is about taking abstract information and representing it visually. The technologies we use to create these visuals encompasses TV, mobile, full-blown virtual reality and all that lies between.

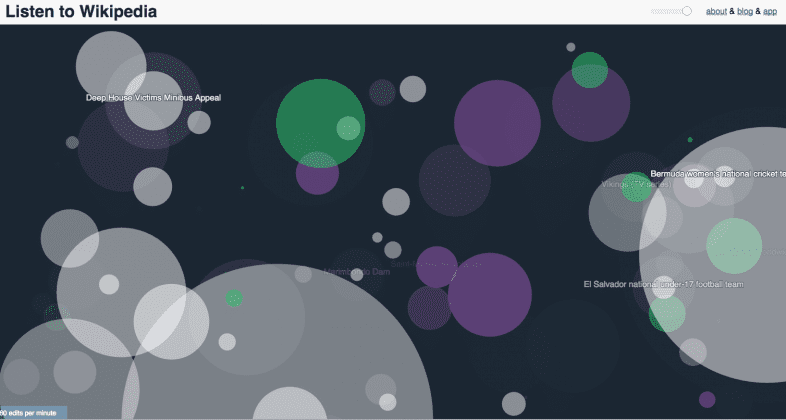

Our brains are hardwired to think in images, Lugmayr explains. “We don’t think in abstract. We think in pictures,” he says, so it makes sense to turn complicated data and information into a form, or visualisation, that is easier to understand. Aside from its entertainment value, it is particularly useful for visualising data, scientific information and information systems. Visualisations can range from a simple pie chart to complex virtual environments, such as the 360 virtual tour of the proposed design for a new pedestrian bridge in central London, or one of the 15 data visualisations of Wikipedia.

Related: Find out about big data and how Curtin researchers are visualising it.

“Visualisation and the technologies that enable it allow us to interpret more complex aspects of data and information,” Lugmayr says. It has a huge range of uses, from mapping crime and analysing financial markets, to keeping track of customer relations in sales and monitoring and controlling manufacturing systems.

“In the last few years, we’ve seen new visualisation technologies in the form of Google Glass, Microsoft HoloLens and Oculus Rift. It is already becoming a major technology. It is present almost everywhere and is rapidly increasing.”

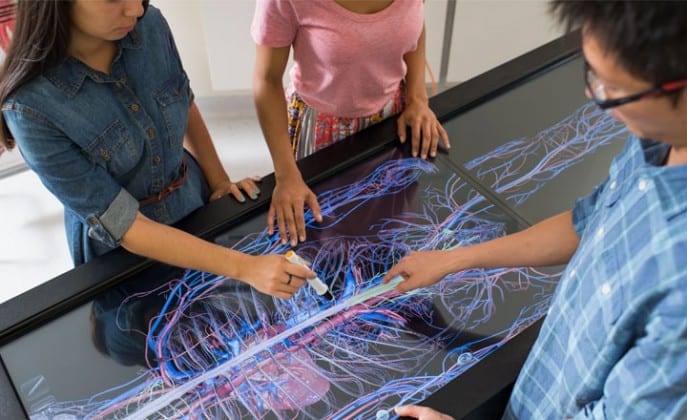

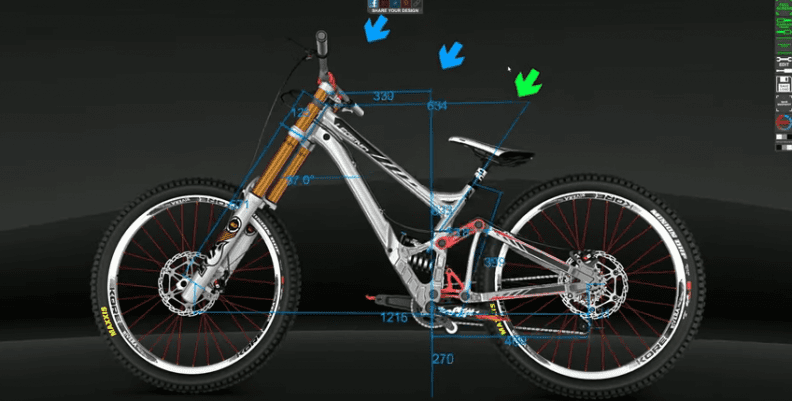

In the United Kingdom, the British military is using virtual simulation to train its soldiers, while in Singapore Elementals Studios have designed the 3D Bike Configurator – a 3D manufacturing interface that allows cycling enthusiasts to customise a mountain bike to their liking. Closer to home, cultural heritages are being digitised and preserved for a new generation in the form of interactive and virtual museum exhibits, such as the Curtin and Western Australia Museum’s project, Two Lost Ships, and the Gallipoli in Minecraft installation at the Auckland Museum. In health and medicine, interactive Anatomage tables are also providing virtual cadavers that train Curtin’s own health sciences students in anatomy.

While the VisMedia course is still the new kid on the block for Curtin, it hasn’t stopped Lugmayr’s students from exploring the possibilities of this new emerging field. They’ve built virtual realities with Unity Game Engine, visualised horror movie data in 3D at the Curtin HIVE (Hub for Immersive Visualisation and eResearch), and experimented with multi-view sports broadcasting that allows the views to switch between players, player biodata and game analysis.

Students and researchers use the Curtin HIVE to showcase and visualise their projects.

VisMedia students use Unity Game Engine extensively in their studies. Used by professionals from a number of industries, Unity Game Engine is capable of creating 2D and 3D games and interactive experiences.

“I love all things tech,” says third-year student, Alex Tate. “The opportunity to be at the forefront of such rapid growth and change is exciting – though at times it can be daunting going all-in on an industry that doesn’t fully exist yet.”

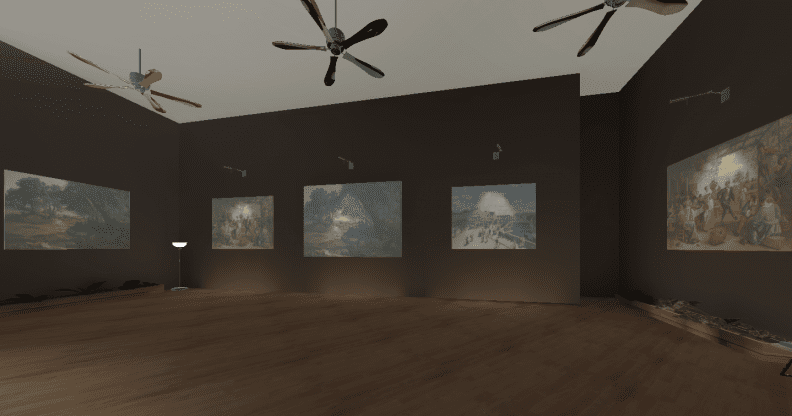

As part of their end-of-year group project Tate and a team of five other students: Lorenz Borraccino, Matilda Fry, Stevie May and Toby Williams, recreated the John Curtin Gallery in virtual reality. Using an Oculus Rift headset, the project was designed as an informative display for arts festivals where people from across the globe could explore and interact with the John Curtin Gallery’s art pieces. After some trial and error using photogrammetry – a technique that generates a 3D model from 2D photographs – Tate and his group opted to build the virtual gallery from the floor plans of its real-world counterpart.

“After that my time was spent tweaking the lighting, texturing everything, populating the room with 3D models, putting paintings on the walls, coding sliding doors and ‘painting-portals’,” he says.

Watch: See the John Curtin Gallery virtual reality in action.

“I’ve been able to use what I’ve learned in the course outside of an academic environment to work on my own artistic practice using virtual reality and 3D modelling/game engine software.”

Fellow student, Matilda Fry, has been exploring how to visualise live biodata to generate interactive artworks and responsive virtual environments. Her first project, Darta (a wordplay on data and art), saw her create a wearable device that incorporated a temperature sensor and accelerometer. The device, worn on the back of the hand, picks up the heat and motions of its wearer and visualises this data it as a circle on a screen. As the wearer gestures, the circle moves and if it is particularly hot out, or the user has clammy hands, the circle will change colour in response.

“Darta is not just data visualisation, it reminds us of the beauty of being human by allowing us to look at ourselves in a way we never have before,” says Fry.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SMH0Z6MCwzI][/youtube]

In her final group project, this idea was taken a step further. Rather than an interactive screen, Fry together with Adam Greenfeld, Joshua De Boer and William Hobbs designed an entire virtual environment. Like Darta, this virtual environment also changed according to a live feed of biodata. Using an Arduino Uno motherboard and the open-source software and programming language that came with it, Fry developed a virtual landscape that responded to the data it received.

“Every day we learn about things that are changing the way we interact with technology and pushing the boundaries of how media can be used to connect with people,” Fry says. “We learn practical skills such as programming and prototyping, which allow us to bring our ideas to life. Business skills are also covered as we need to plan our projects, work together, pitch ideas, and ensure they’re organised well to be ready in time for presentation.”

Lugmayr describes VisMedia as a convergence between business and management, content generation and technology. “It is a visionary and a future orientated program and we integrate all the latest trends,” he says. “Students learn a set of approaches, tools, methods that allow them to apply their knowledge across disciplines. They also learn to communicate between professionals such as designers, engineers, architects and finance specialists.”

In essence they are intermediaries, the designers and translators of visual information.

“There are applications in medicine, for example, in virtual operations. They need people who know how to make the graphical interfaces. So while VisMedia is not a medical degree, it can still support others who work in medicine and health, or in architecture, archaeology and education for that matter.”

Currently VisMedia is mostly used by the creative industries, but as other industries adopt interactive technologies graduates could find themselves working in a variety of settings. While a recent seek.com search turned up studio and agency opportunities, visualisation specialists were also being sought in areas such as financial services, human resources, real estate, commerce and architecture.

So if you’re keen to don a pair of VR goggles, or help scientists visualise hidden galaxies: the future is knocking, and VisMedia could help you answer the door.