Curtin Sarawak is empowering communities in the highlands of northern Sarawak on the island of Borneo. As part of their Rural Development Plan, Curtin Sarawak is planning a number of new schemes to bring power, water and new business enterprises to some of the most remote villages in Sarawak.

Heading the project is Professor Clem Kuek. After working and living in Australia for 35 years, Kuek has returned to Malaysia looking for ways to give back to the communities of his homeland.

Lights on

Located in the mountainous regions north of Sarawak, villages such as Long Tanid, Long Muboi and Long Rusu have no access to grid electricity. Individual households have to install diesel generators. The diesel fuel for these generators has to be transported from distant urban centres via a rudimentary road network (often little more than logging tracks). Now, through the introduction of green technologies such as hydro and solar power, these villages can have access to clean, green power, 24/7.

“Before we only had a few hours a day and it was very expensive,” says Puden Burele from Long Rusu village, where a community-run micro-hydro electricity system was built in 2014. Plans are in motion for Curtin Sarawak to build similar systems at Long Tanid and Long Muboi. Unlike previous schemes, the Curtin Sarawak systems will be combined with the supply of potable water, another utility which rural communities are also lacking.

Unlike large hydro schemes, a micro‐hydro does not require a large dam and associated reservoirs, which can interfere with river ecosystems. Instead a micro-hydro system diverts water away from the main stream, filters it and then flows it down a pipeline and into turbines housed in a small powerhouse. Once through the turbines the water flows back into waterway further downstream. Micro-hydros are green, reliable, cost‐effective and low maintenance. As such, they are seen as one of the most suitable ways to bring electricity to rural communities.

The local communities will be vital to the success of the project, Kuek explains. “They will help us build the systems. After we hand over the project they’ll be able to maintain and run it on their own.”

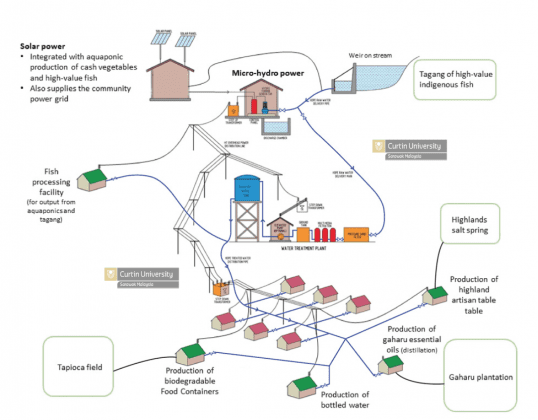

But these power projects aim to do more than simply improve home comforts. These hydro and solar power systems are the heart of Curtin Sarawak’s overarching rural development scheme. Following the installation, community-owned enterprises will also be introduced to build upon the availability of electricity and clean water. Using the resources already available in the highlands, these enterprises will aid the region’s salt production and indigenous fish-farming schemes, as well as open up new opportunities for the local production of bottled water.

Something as simple as having power to run a refrigerator means that businesses in food production, trade and transport are able to start up and grow. It also means fewer trees are felled for use as firewood in a process for preserving food.

“It is has been very useful for businesses,” Puden Burele says. “Food is no longer being wasted in the same quantities as before. Less trees are being cut for firewood [used for food preservation], which means less air pollution and damage to the ecosystem.”

A real bottler

Another opportunity for the region is to use the micro-hydro electricity and potable water to create a community-owned water bottling business.

While mountain streams surround many villages, the water must first be boiled and filtered to make it clean enough to drink. It’s a tedious process, so bottled water is used instead, trucked in from Miri and Kota Kinabalu.

“The [bottled] water is transported over many miles of logging tracks to get it up there. And by the time it gets up there, it is double the cost,” Professor Kuek explains. “So we asked: ‘Why don’t we help them bottle their own water?’”

“We’ve proposed setting up a model water bottling plant,” Kuek says. The plan, costing two million Malaysian Ringgit (approximately AUD$702,000) comes in two parts. First and foremost is to provide the communities in close proximity of the plant with cheaper, more accessible bottled water. Thanks to the largely pristine environment of the highlands, the second stage hopes to take this concept and use it to market the bottled water to the wider region, including to the urban centres.

Although some countries have expressed concern over the environmental footprint of bottled water, it is still a vital life essential to the northern Sarawak communities and will continue to be consumed there simply because there is little alternative.

“The difference now is that they’re making it themselves and earning an income for their community,” Kuek says.

Bottling water is a means to get communities to master their own resources and become more economically sustainable. A bottled water enterprise would develop entrepreneurship and bookkeeping skills within the community, strengthening it as a whole.

Power for premium salt

The northern Sarawak power schemes are also set to lend a hand to the salt producers of the highlands.

“Rock salt has been produced in the highlands for generations,” says Kuek. As a niche product, similar to rock salt from the Himalayas, it is highly valued.

The salt is created from brine, a solution of salt and water, which is brought up from wells and piped into large drum-like kettles and boiled over three days to produce around 60 kilograms of salt per batch.

Firewood has been used to boil the brine, and the amount needed to for three days burning is significant.

As part of Curtin Sarawak’s Rural Community Development Plan to improve the region’s salt-making, Professor Kuek and his colleagues are planning to power the kettles and evaporators with electricity from micro-hydro generators.

“We’ll save an enormous amount of firewood and it will be less polluting. The end product will also be much cleaner,” Kuek says.

Fishing for the future

The village of Long Lidong in northern Sarawak is one of several villages that have a “tagang” fish conservation scheme. The scheme involves villages conserving the native fish along a section of river close to them. A major part of their responsibilities is to control the number of fish harvested so as to keep the fish population at a sustainable level.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xtvIq9XtSMs[/youtube]

Many tagangs include protected species, such as the Ikan Empurau and the Ikan Semah, which are highly valuable due to their dwindling fish populations and highly coveted meat (often described as rich and fruity thanks to their fruit-based diets). For example, the Ikan Empurau, reputed to be the most expensive fish in Malaysia, costs around MYR750 (AUD$260) per kilo.

Professor Kuek and his team intend to help set up additional tagangs and develop regional processing facilities to clean, pack and chill the harvested fish for transport.

“This will not only increase the value of the product, but also create jobs,” says Professor Kuek.

Governing fate

To Professor Kuek, these projects are more than just providing power and water. They’re about moving the communities of northern Sarawak towards being self-reliant and economically self-sustaining.

“We will not be satisfied with just bringing in two utilities to a community,” Kuek says. “We say, if you have access to electricity and clean water, what can you do with it in terms of an enterprise?”

Every project is community driven. With power and water projects at the heart of the northern Sarawak Rural Development Scheme, the locals are its lifeblood. From initial planning and consultation, to building facilities and growing each enterprise, the communities are crucial to every step. Without their support a project runs the risk of being abandoned once the infrastructure is built and external personnel leave.

“We make sure village leaders know what is being proposed, what the implications are, and what the management component of it is,” Kuek says. His end goal is to equip communities with the ability to run these projects on their own.

While there is still the anxious wait to get the final approval for these projects, for now we know that the lights are on and the future is looking brighter already.