In 1978, humanities scholars worldwide were profoundly affected by the release of Reading Television, a book by UK Professors John Hartley and John Fiske, who had drawn on the new sciences of semiotics and linguistics to analyse how TV was playing such an important role in Western culture.

The book challenged the dominant thought of scholars at the time – that TV was not worthy of cultural study – and went on to have an astonishing impact, catapulting both professors to research fame and helping to establish television studies as a new field of research.

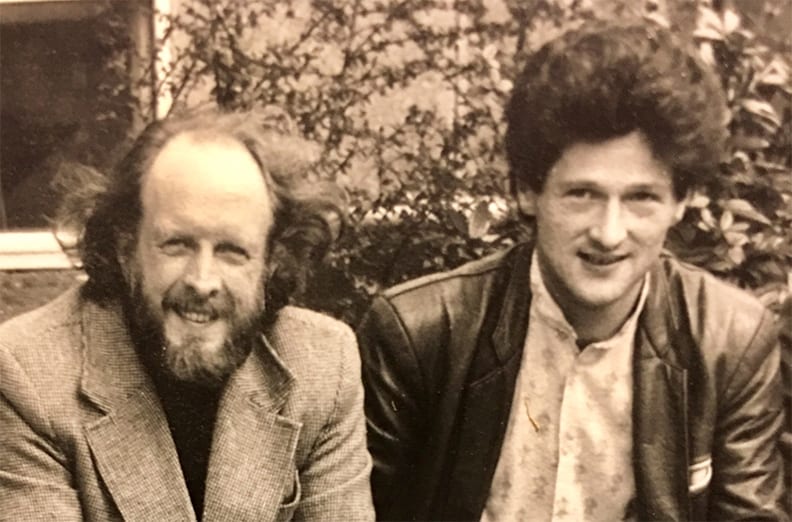

In celebration of Reading Television’s 40th anniversary, we chatted to Professor Hartley, now the cultural science program leader for Curtin’s Centre for Culture and Technology, a Member of the Order of Australia and a John Curtin Distinguished Professor, about his memories of writing the book, his thoughts on its impact and his current research.

Can you begin by summarising what Reading Television is about?

Thanks. Reading Television was a pioneering attempt to study television from the point of view of the meaning of its stories.

Given that the greatest icon of English-language culture, William Shakespeare, was a popular dramatist, and that TV was the most popular dramatic medium the world had ever seen, we wanted to understand it in the same way that literary criticism studied Shakespeare.

At that time, the only studies of popular media came from behavioural science, which focused on TV’s supposed negative effects. We wanted to know what made it attractive for so many. To do this, we adapted approaches from the humanities to analyse meanings encoded into everyday programming, from sport and Come Dancing to news and Bionic Woman.

How did you and John Fiske come together to write about this topic?

John Fiske and I were both appointed to the Polytechnic of Wales as part of a team that developed a new Communication Studies program, only the second in the UK at the time.

Along the way we realised that there were no serious studies of popular media from a cultural perspective, so we decided to research and write the book.

Do you remember having any particular revelations about television and how we perceive it while writing this book?

First of all, we wanted to understand popular television from a cultural perspective. We wanted to know how modern complex cultures communicate with themselves. Unlike the behavioural sciences, which saw popular media as a social pathology, we wanted to know how popular media brought people together.

We were attracted to semiotics and linguistics. We looked for signs, myths and ideologies embedded in entertainment formats, and how these might reinforce or undermine traditional notions of selfhood, social conduct and community identity.

At the level of corporate clout, TV became more influential than the press during this period, gathering huge populations for advertisers. But at the level of the viewing family unit, TV was much more important for cultural identity work.

We discovered that television plays a role in constructing and communicating a sense of who “we” are, collectively, within all the differences of class, gender, ethnicity, nationality, sexuality, age, region, politics or aesthetic affiliation.

What ideas, insights and frameworks are still relevant in 2018, and what do you think has fundamentally changed?

Obviously, with the emergence of digital technologies and social media, broadcast television has changed forever. This centralised form is no longer dominant; now mobile devices and personal screens are ubiquitous.

Many of the insights, methods and findings we pioneered in the 1970s have become mainstream. Communication studies has become firmly established across the world, including at the most prestigious universities.

As long as we in higher education continue to teach students how to use the available media forms for critical engagement and the growth of knowledge, and not just for passive consumption or market manipulation, then we can continue to realise the potential for civic emancipation and intellectual freedom. Just look at The Handmaid’s Tale, Humans, The Slap or Go Back to Where You Came From.

How do you think your book has affected academia?

Well, we did get in at the start of something big! Reading Television was published in the context of two major changes in higher education in the UK and also internationally.

The first was the move to open the curriculum to cover new technologies and service industries that were increasingly significant to the economy, including the media. The second was the decision to open higher education to more students, not only to improve the capability of the workforce but also to extend opportunities across old-fashioned class, gender and ethnic lines.

It has to be said that the most prestigious universities were also the most resistant. Vocationally oriented polytechnics and institutes of technology like WAIT in Australia took the lead, teaching new things to new students, most of whom were the first in their families to attend college.

At the same time, we drew our methodology from numerous existing disciplines, bringing social and technological sciences into close contact with the arts, humanities and cultural critique for the first time. Eventually these interdisciplinary approaches evolved into stand-alone disciplines, which have become popular, influential and increasingly rigorous in their own right.

You are now the program leader of cultural science at Curtin’s Centre for Culture and Technology (CCAT). Can you describe exactly what cultural science is, and what you’re hoping to achieve as program leader?

Cultural science is an attempt to develop a systematic and evolutionary approach to cultural phenomena. It’s all part of a much longer process of “de-centring” the human individual.

That process began in the Renaissance – with Copernicus decentring our place in the cosmos – and has continued throughout modernity, with Darwin, Marx and Freud, who demonstrated that the individual is not the author of their own life, history or consciousness. It is clear that culture does not belong to a person or even a nation, but is globally distributed.

In this context, culture needs to be seen as a planetary and interspecies phenomenon. It is clear from Artificial Intelligence and robotics, as well as from new work in “post-humanist” studies led by Matt Chrulew at CCAT, that culture cannot be confined to humans, but applies both to other lifeforms and to AI.

How these large-scale, evolutionary systems work, and how we can make the best use of them without destroying the environment, is the objective of cultural science.

On a practical note, Cultural Science is also a new journal, recently relaunched by CCAT, in which some of these ideas are explored.

You’ve authored 30 books, but Reading Television was your first. What does it mean to you?

Reading Television remains an important turning point for me. I was trained in the literary and historical study of Shakespeare and Elizabethan drama. But with this book, John Fiske and I applied that training to the popular drama and storytelling of our own times.

This caused quite a stir. Reading Television was reviewed in every type of outlet from the daily newspapers to Time Out. It has been adopted for courses throughout the world. It went on to become a major international bestseller and has been translated into many languages.

It has never been out of print since the day it was published 40 years ago, and is still cited in media research, with more than 2,000 citations on Google Scholar.

If you’re interested, you can purchase the book from Routledge and other online book sellers, or borrow it from the Curtin University library.