Reading time: 6 minutes

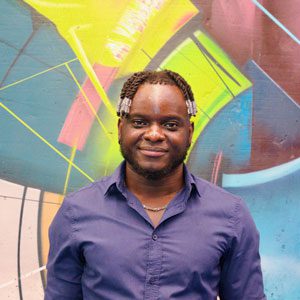

As a field geologist and researcher, Legran is connecting continents – both scientifically and literally. From France to South Africa and now Curtin Perth, his journey spans rocks, borders and breakthroughs. Studying ancient eclogites, he’s helping to decode Earth’s deep past and strengthen global ties in geological research.

Legran Plavy Ntsiele is currently completing a PhD in the School of Earth and Planetary Sciences (EPS) at Curtin University, co-supervised by Curtin’s Professor Chris Clark and Professor Ian Fitzsimons, and University of Adelaide’s Professor Alan Collins. Legran and Chris reflect on the challenges of sampling rocks from around the world, the importance of building international relationships and their working relationship.

Legran:

I did my Bachelor in France at the University of Montpellier. After that, I went to South Africa, where I did my Honours and Master, before coming to Australia to do my PhD. Curtin has one of the best geology departments in the world and they have a very high-tech facility. That was one of the main things that drove me to study here. I wanted to carry on doing research and learn some new techniques, especially like geochronology and things like that. And the geology department has everything hands-on. You can do every single experiment you want to in a lab here, so you don’t have to go anywhere else.

For my PhD project, I am looking at high-pressure rocks, known as eclogites, within the Zambezi Belt in Zambia. These rocks were formed around 500 million years ago and give us a clue about the formation and the destruction of a supercontinent called Gondwana. My research involves studying these high-pressure rocks to try to reconstruct and refine models of this supercontinent.

The formation or break-up of a supercontinent like Gondwana triggers mountain building, ocean closure and volcanic activity, which are processes that profoundly impact the atmosphere, biosphere, and the formation of mineral deposits. So, reconstructing Gondwana can provide valuable insights into past climate evolution, ocean circulation patterns, ecological niches and the distribution of mineral resources.

The main challenge of the research was getting rock samples out of Zambia. It was not because I didn’t have a permit to transport the rocks, it was because the airport and the Geological Society of Zambia didn’t connect. It’s rare for people to try and take rocks out of an airport. It looks strange. The airport staff hadn’t seen a permit like mine before – so they were immediately suspicious. We managed to sort it out eventually with the University of Zambia’s help. If we hadn’t contacted them, we would have been stuck.

A geology PhD is incremental to some degree.

The big things will come, the research outputs and the data will start to take shape now that we’ve got samples and done the basic petrology; looking at those rocks and deciding where we’re going next with them all. A successful field season anywhere in the world is a good thing to have happened.

Once we finish the basic petrology work, we’ll move on to dating the rocks and estimating the pressures and temperatures they experienced, using accessory minerals like zircon, rutile, and titanite. These minerals help us track when and how the rock has changed over time. By combining this information with existing data, we’ll use numerical modelling to piece together the full history of how Gondwana formed in southern Africa.

The highlight of the PhD so far was spending two weeks driving around Zambia, sampling and touring around. Although we went there to work, we also took some time to visit the country and do some tourism activities. We went to Victoria Falls and even did a boat trip on the Zambezi River, which was really nice.

Chris is very laid back, so the thing with him is you need to be proactive. If you want something, you can just go and see him.

Chris:

I advertised this project through a website called Earthworks. I was looking for a PhD student who could go and do fieldwork in Africa and negotiate to get rock samples, which takes time and patience. We ran a competitive interview process and Legran was selected based on his previous experience in his Master doing fieldwork in Africa.

Field work is an important part of a PhD in my area because you not only have to go out and get the rocks, but it also requires an understanding of how to identify what to collect, how to sample and how to bring it back. Legran had that, but also with a degree of independence as he had done a Master project in the Congo Rainforest.

Getting rocks across borders is challenging, especially from countries where they may or may not have mining industries or understand why you’re trying to take rocks from their country and think that everything must be valuable. Whereas they’re not really; they’re just rocks to us. Negotiating and explaining is something that’s great to have experience in if you’re going to do a PhD. Legran had that – and demonstrated those skills when he was stopped at the Zambian border.

Although we thought we had all the paperwork together, he had to leave his rocks in the airport, get on the plane and come home. That was his PhD sitting in a box in an airport with no control. But the University of Zambia, the people there, were able to eventually facilitate their movement back to Australia. We couldn’t have done that without the relationship Legran had established.

I would say my supervisory style is laissez-faire. I’m very relaxed about my supervision. I will endeavour to put as many resources as possible in place at the start and a broad framework so everyone can see the goals of the project. I’m happy to provide advice along the way but I don’t like to be too prescriptive. Sometimes that’s a challenge because some students really want to be told exactly what to do. I strongly believe that’s not a PhD.

A PhD is: you go and discover what it is that you’re interested in, what you want to do and you do it.

It’s where the data takes you or where the rocks take you. And if you’re good at it and you like it, you’ll do it.

When I’m in my office, my door is always open. People can wander in; you don’t need a meeting request to come and see me. When I’m in my office, I’m usually happy to take five minutes away from whatever it is I’m doing to chat about it.

About the researchers

Legran Plavy Ntsiele

Legran is a second-year PhD student specializing in geochronology and metamorphic petrology. His research focuses on the P-T-t evolution of eclogites and whiteschist in Zambia’s Zambezi Belt to refine Gondwana assembly models. He is also engaged in scientific outreach, student mentorship, and international academic collaboration beyond his research.

Professor Chris Clark

Chris is a metamorphic geologist and geochronologist, his research integrates techniques and data from the fields of geochemistry, geochronology, structural geology and tectonics. He is currently working on an ARC Future Fellowship project investigating the role that Supercontinent formation plays in driving extreme metamorphic events.