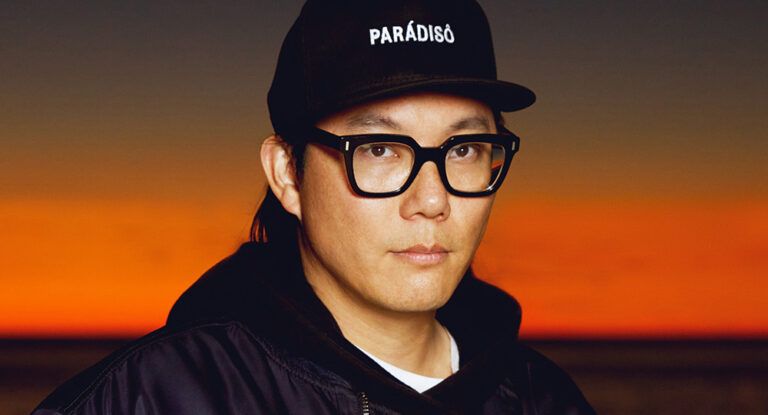

How did your journey into the art world begin?

As a child, I remember when we moved into a new home and there was this huge cardboard box from our TV.

My Mum showed me how to turn it into a pretend house.

We drew the door, windows and coloured in a multicoloured roof, and she showed me how to use a box cutter for the first time. That kept me entertained for days!

That moment has stuck with me my whole life, I’ve been so fortunate to have a Mum who has always encouraged me to use my imagination with everyday life and moments.

What is the purpose behind your art?

Identity is an important part of my art, particularly the story of immigration.

Especially navigating dual identities, balancing heritage and culture with that of a new country, is challenging.

Sometimes we can feel a societal pressure to conceal or abandon our home culture.

When you move to a new country, as a child, all you want to do is fit into the new culture.

However, if it weren’t for the right influences in my life, I would have lost that culture. There is a power in preserving your identity.

Growing up, I was never embarrassed by my family, but I saw other Asian kids being embarrassed by their grandparents or parents walking them to school.

I knew one kid who never invited any of her white friends into her home, as she lived in a very Chinese household. Her parents spoke Mandarin, the food they ate was very different to what white kids would eat, and the furniture was very different. At times, there’s a quiet but persistent pressure to hide that.

I found that art was a quiet but persistent way to reclaim and affirm my identity.

Through my art, I wanted to show the possibility that you can be in a Western country and still maintain your Chinese identity and participate in tradition and culture.

My art is not a manual; it’s simply there to show others that they are not alone.

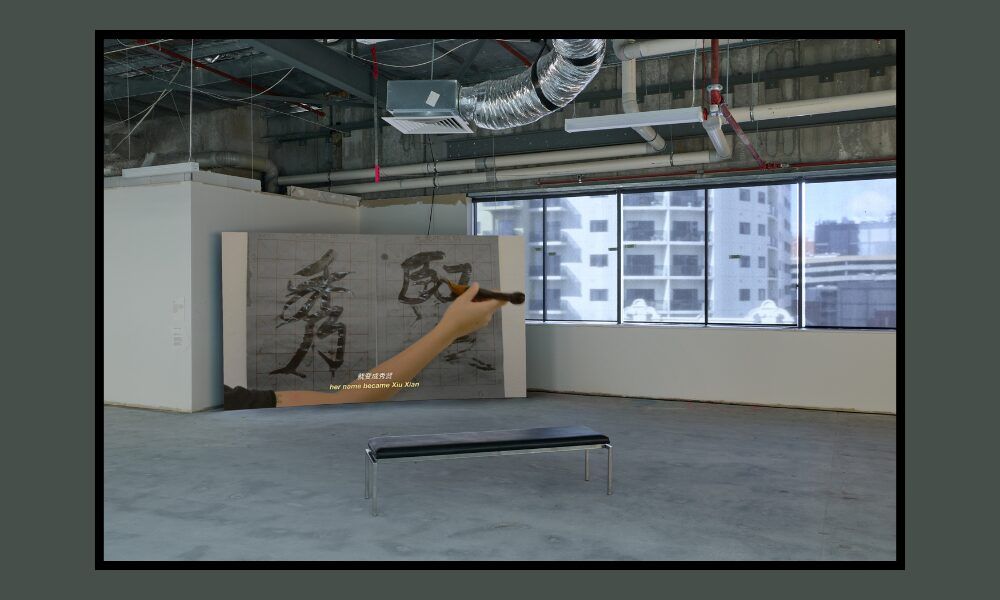

This motivation to create stems back to the love I have for my family. I always think about how sad it would be to miss out on having closer relationships with your relatives from back home simply because you can’t communicate with each other, which is I created ‘her name, an anthology’.

Can you share your creative process?

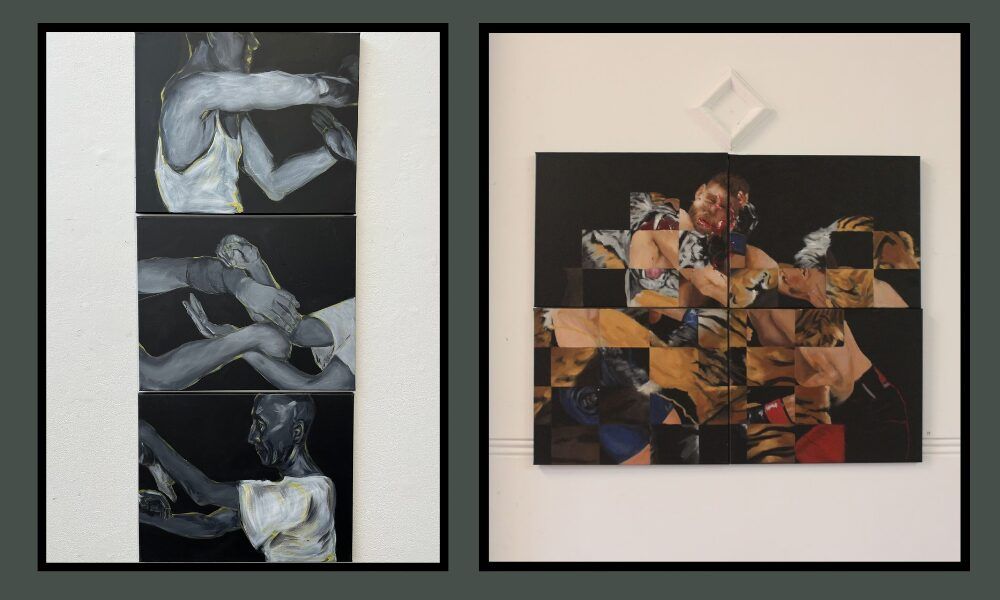

My creative process changes a lot depending on the project.

Sometimes ideas come to me in dreams, randomly mid-conversation, when I’m driving to work or walking my dog.

I try to write my ideas down in my journal, but most of the time they just sit there. Sometimes, I’ll want to explore it more and will get my paints and coloured pencils to do some sketches. Then, I’ll leave it alone for a while, and when inspiration strikes again, I’ll develop it further.

I have a lot of unfinished projects. Most of my creative process involves a lot of problem-solving, like I usually have an end goal in mind – not always a visual end goal, but more like how I want it to feel in the end, and the creative process is just figuring out how to get there.

What is your most favourite project that you’ve worked on to date?

My most recent piece, ‘her name, an anthology’ has a special place in my heart right now.

It’s the first project I truly felt very deeply connected to and received much success with.

I’ll admit there is still a lot that I don’t know about the art world than what I do know.

Although this can be daunting, I just try to remind myself of a young Grace making houses out of cardboard boxes and the importance of just having fun. It never works well for me when I create out of fear, but I can learn to find joy and be open to learning.

How has your Fine Arts degree helped shape you into the artist you are today?

Having my own space, even though it was shared with others, was so freeing.

Just being able to create and be with others while we all make things was such a positive and inspiring experience.

Magical things always happen when you put a whole bunch of artists in a room with no limits to what they can make (well, except for the rubric, I guess).